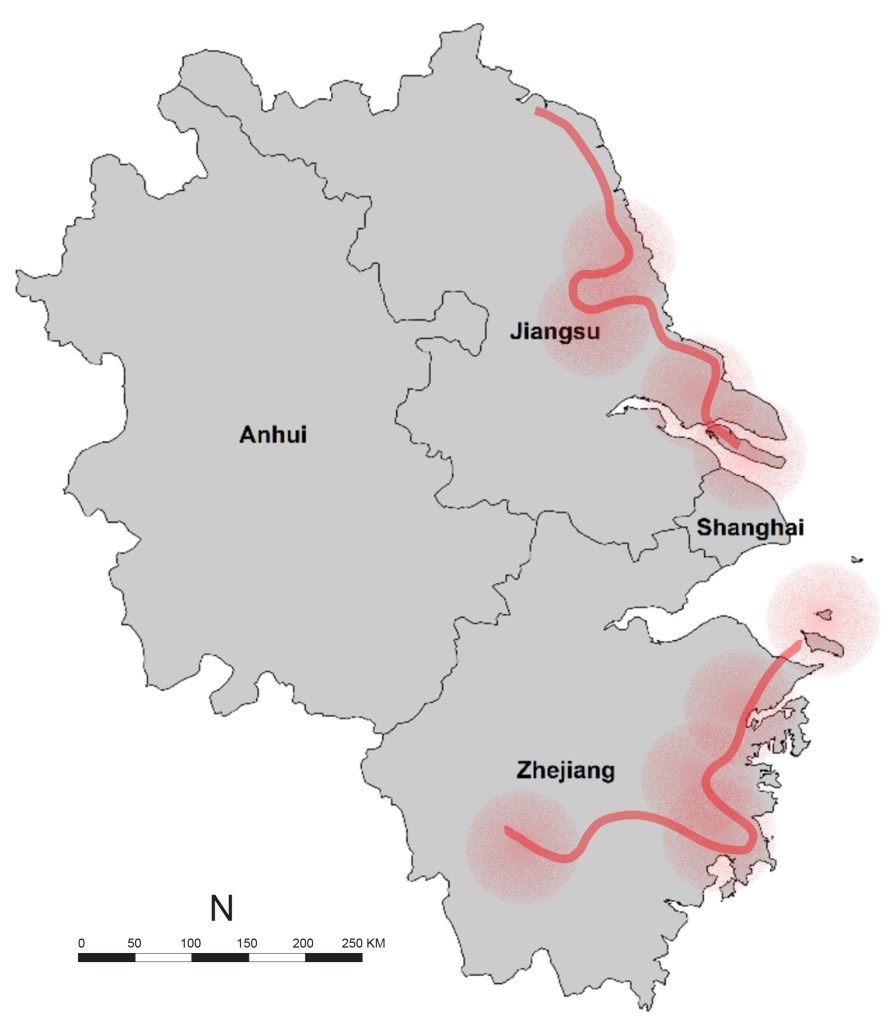

主要步行路线的指示,作者图片 Indication of the main walking route, image by author

(中文翻译在英文正文之后)

October 2023

I still remember my first visit to Shanghai over two decades ago. I was overwhelmed by the then sparse yet futuristic buildings rising above the old city, with only a handful of bank towers in the financial center, Lujiazui. Taxis buzzed through the streets—Volkswagen Santanas with polluting gasoline engines. Private cars were rare. Rows of mostly blue-painted trucks, many from now-defunct brands, filled the roads, loaded with building materials and surrounded by clouds of dust. Noisy, non-electric mopeds completed the scene. At the end of a day spent walking through the city, I would wipe my face and find my nostrils and ears smeared with a thin black film of gunk. At the time, few people thought about the consequences of pollution—certainly not me, a country boy from the Dutch polder, numbed by the cosmopolitan spectacle.

Almost a decade later, shortly before Expo 2010 in Shanghai, I first heard someone voice concern about the deteriorating air quality. It was during a conversation with the head of a large international design firm, who was deeply worried about his children’s future. Not long after, he returned to the United States with his family. During the Expo, international media increasingly published critical articles about poor air quality in Chinese cities. But what about the role of Volkswagen, the many international agencies in the construction sector, or the relocated industries from the Global North that benefited from China’s less stringent environmental regulations?

Over the past two decades, Shanghai has experienced explosive growth, adding around ten million inhabitants during the time I’ve lived there. According to the city council, Shanghai has now reached its growth limits, prompting the introduction of a population cap. Red lines have been drawn around the city to prevent further urban expansion and protect rural land. Since Expo 2010—ironically themed Better City, Better Life—almost all polluting industries have been moved out of the city. An Ecological Civilization is now expected to be achieved within a few years. Despite—or perhaps because of—its rapid economic catch-up, China is currently leading global efforts to tackle the climate crisis, though not without caveats. Beyond criticism, can we also learn from China’s approach?

Recently, amplified by strict COVID-19 measures Shanghai’s population has begun to decline. Problems in the real estate sector, combined with international economic shifts, have tamed the building boom and slowed consumption, with serious consequences for the city and its citizens. Countless migrant workers from rural areas have left, as have many others. Will the city ever regain its cosmopolitan character? Will the countryside become an outlet for those leaving the city, shifting the urban-rural dynamic once again? More importantly, and paradoxically, how can the countryside be protected from renewed exurban pressure now that Shanghai and other metropoles appear to have reached their limits?

I have long studied rural issues and urban-rural relations around Shanghai, particularly in the context of new town development and waterfront revitalization. My previous research focused on rapid growth, prosperity, and the shift from rural to urban lifestyles, with real estate speculation causing significant tensions. Today, the dynamics have reversed. In the face of new challenges—including the energy transition, climate change, agricultural concerns, lack of affordable housing, socio-economic inequality, and potential population shrinkage—I continue to explore rural (and inherently connected urban) phenomena. I do this through investigative rural walks far outside the city, reflecting on and searching for sustainable alternatives for exurban and rural areas.

2023年10月

我还记得二十多年前我初来上海的时候,完全沦陷于老城乡拔地而起的零星的未来主义建筑,和在陆家嘴金融中心数得清的几座银行大楼。大众桑塔纳出租车在街上嗡嗡作响,汽油发动机污染严重。几乎找不到私家车。街道上挤满了一排排卡车,卡车大多漆成蓝色(部分品牌已消失),满载建筑材料,周围尘土飞扬。我的照片里到处是不计其数嘈杂的非电动轻便摩托车。在结束一天的城市漫步后,我的鼻孔和耳罩上覆盖着一层薄薄的黑色粘呼呼的东西,当我用手指擦拭它们时,我才注意到。当时几乎没有人想过污染的后果。至少我没有,作为一个来自荷兰滩涂的乡村男孩,我被世界性的景象弄得麻木了。

大约十年后,在2010年上海世博会前不久,我第一次听到有人对空气质量的恶化表示担忧。这是在与一家大型国际设计公司的负责人的私人交谈中,他表示了对自己孩子未来的关切。不久之后,他和家人回到了美国。在2010年世博会期间,国际媒体越来越多地开始发表关于中国城市空气质量差的评论文章。多数直指大众汽车的作用、众多建筑行业的国际代理机构,或从全球北方迁移过来的不必遵守中国严格环境法规的工业等。

在过去的二十年里,上海的人口成爆炸式增长,在我居住期间增加了大约1000万居民。根据市政府的说法,上海现在已经达到了增长的极限,并引入了人口上限。为了防止城市扩张和保护农村土地,城市周围已经划定了红线。自2010年世博会以“让城市更美好,让生活更美好”为主题以来,几乎所有污染行业都已迁出城市。生态文明必须在几年内实现。尽管是因为中国的经济追赶(或者可能是因为经济原因),中国目前在应对气候危机方面处于领先地位,虽然伴随一些警告。所以在批评之余,是否也可以从中国的做法中吸取一些教训?

在遏制新冠肺炎的无情措施下,人口最近开始减少。同时房地产行业和国际发展问题的刺激下,建筑业的繁荣和消费势头在一定程度上受到了抑制,给城市及其公民带来了严重后果。无数来自农村地区的农民工和许多其他人一样离开了城市。这座城市还会像不久前那样国际化吗?农村会成为一个发泄的出口吗?城乡关系会再次发生变化吗?更重要和更矛盾的是:既然城市似乎已经到了极限,如何保护农村免受这种新的(逃离城市)压力?

我以前研究过农村问题,也研究过大都市上海周围的城乡关系,尤其是新城开发和滨水振兴的研究。这些研究都是关于快速增长和繁荣,以及从农村到城市的生活方式变化。房地产投机尤其导致了紧张局势。今天,情况正好相反,新的挑战朝向了例如能源转型、气候挑战、农业挑战、缺乏保障性住房、社会经济不平等和可能的经济萎缩等。我将继续研究农村现象。特别是通过在远离城市的乡村进行研究性徒步来实现这一点,以反映和寻找远郊和农村地区可能的可持续替代方案。